HARD LESSONS

The Okuku Range is a cluster of hills 900m-1100m high, rising from the northern limit of the Canterbury Plains and treading north-westwards to meet the foothills of the Puketekari Range. Jack grew up in the Okuku Pass which runs between it.

I used to walk down to the White Rock limeworks to talk to the people over there or the men on the station, but I suppose I was a lonely kid in a lot of ways. I’d sit on the tractor with our neighbour Harry Gudex – helping with the farmwork. Used to go there for mercy every now and again. I was a loner but I enjoyed the men – seemed to get on with them and they didn’t seem to worry too much what I did.

For six weeks each summer from 1932 to 1934, we went to a holiday house at Leithfield Beach. But it was an awful place, with no conveniences whatsoever – an outside loo, kerosene lamps and primus cooker. I was absolutely infuriated with this – couldn’t stand the salt water or the sea, and I was a permanent pest there… perennially in trouble. Whenever we were there I couldn’t get back to the shearing quick enough. I loved it in the shed – flat out with the men – cutting dags off wool, whatever I could find.

As for school, Jack was intitially taught by governesses because the nearest school at North Loburn was too far away. His most memorable governess was Miss Clulee, who took classes out of an old traction engine cabin.

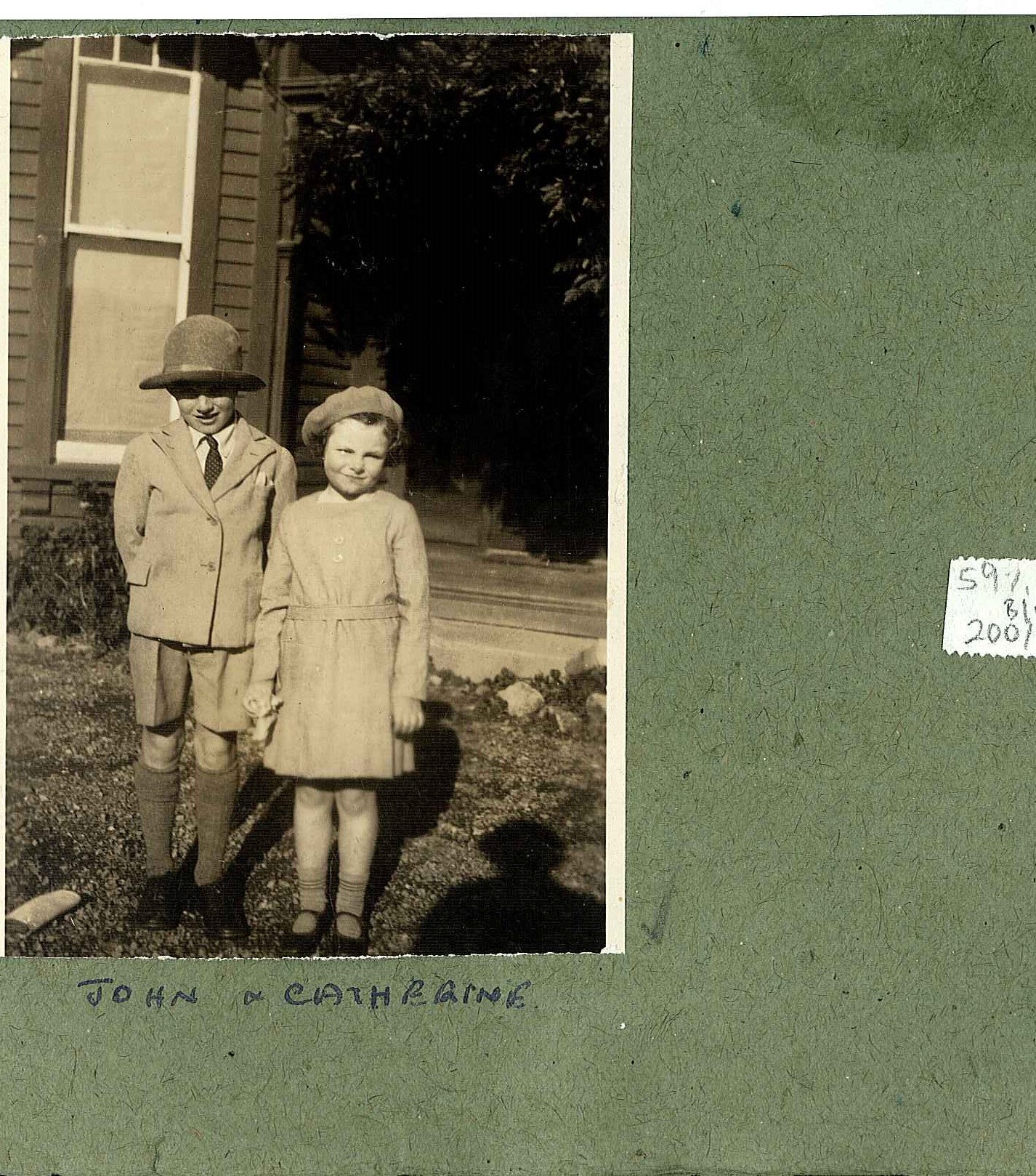

She was a tremendous person – thin as a trowel but we managed to get on pretty well together. She didn’t have to chastise me or anything; reined me in, put it that way. She taught me how to read and to appreciate books and that sort of thing. A couple of the other kids up the road came down to join us, and Katie started there as soon as she was old enough.

When he was 10, the family sailed on the “Wanganella” to Sydney, and then to Melbourne.

She rolled and dived all the way over, and by the time we got to Sydney the lifeboats had been wrecked, the railing had gone and she was in a real mess. Eventually we headed to Victoria and stayed with Winifred’s mother, Granny Austin. She was a fearsome woman, she really was. One time she sent me down to the shop with a pound, which back then was a close to a week’s wages, and when I walked in with a pound note, the shopkeeper thought ‘Hullo, he’s nicked this’. I bought my things and worked out on the way home there were 10 shillings missing – about three days wages. I reported this to Granny Austin, and she grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and dragged me down to the shop. Granny was probably this shopkeeper’s best customer, so you can imagine the look on this poor chap’s face. I’ve never seen 10 shillings come out of a till so fast. But she really did deliver him an address.

A week after the family came home, Jack was packed off to boarding school at Waihi – a boys’ boarding school in South Canterbury.

We took a special trip to the garage to check that everything was alright, because the roads south of Christchurch were still shingle. I had never sat on a school bench in my life, or had any other boys to mix with, but finally we arrived at Winchester, and I was simply left there. I think my parents were only too bloody pleased to see me go – I don’t think there were any great tears or anything. But it was a cultural shock, really, because suddenly I was pitched into what was just a house and one other building, with an old thatched hut in the playground. The outside loos were way in the bloody distance, 100 yards away from the school. We really used to enjoy our days out, because they didn’t come around often. The only time we had leave was on Sports Weekend; there were no mid term breaks or anything.

My first year we went ice-skating at the Rangitata Gorge and I fell on my face and broke off my front tooth. I was driven back to Waihi with a nerve exposed, and they left me for a week until the headmaster Stonewigg plucked up the courage to drive the car into Timaru to see the dentist.

About 12 of us were new boys, and it was tough going…straight out bullying most of the time. One senior boy was particularly nasty, but finally he was called to see the headmaster. He opened up this boy’s case on the desk, and inside there was every known means of smoking imaginable. So he paddled him with 12 on the arse – a record at Waihi with a jam spoon.

One of the great days, though, was the Medbury cricket match at the Ashburton Domain in 1937. Medbury were largely city boys from Christchurch and we were definitely the country boys – Waihi was much smaller at any rate. Anyway, we made about 49 and Frank Chellor, the Medbury headmaster, chortled and thought what a wonderful match this was going to be… But someone had watered the pitch the night before and then it was a hot nor’west morning. By the time Medbury batted the ball was turning at right angles. I was keeping wickets, and the ball was leaving me for dead half the time. They were all out for nine and Chellor went absolutely berkers.

The same year we were the first at the school to play rugby, because before that there had been too many stones on the ground. Only one of us had played before, Max Henderson from Oxford, but finally we picked up the rudiments of the game and put a team together. There were only 48 boys at the school so we were scraping the barrel a bit. Again we played at the Ashburton Domain, and the two Medbury locks who came out of the dressing room must have been close to 10 stone, which back then was quite hefty. One finished up as a professor of Latin at a top American university but I swear the other, Bruce Ensor from Cheviot, was shaving at the age of nine. They scared the living daylights out of us. But away we went, and our fellas Peter Moore and Max Henderson ran rings around Medbury. It finished 44-0, in the days when it was three points for a try. At half time the two Medbury locks were in tears.

Andrew A. Anderson, who was at Waihi from 1937-41, met Jack on his first day at school. As he explains, he was immediately unnerved by the experience.

“The year 1937 saw some big changes in Waihi School, but standing on the Christchurch Railway Station on March 3rd, I was not to know all that. Travelling down with John Fulton and Hugh Montgomery, supposedly to “look after me”, I was regaled by tales of hardship and oppression that were to be my lot and was thus scarcely in the frame of mind of an Israelite entering the promised land by the time Winchester Station was reached.

Being picked up in the old dray confirmed rather than allayed my fears, thus the school and its grounds were a pleasant surprise. March 3rd was a curious date, dictated by the fact that there was a great polio epidemic raging at the time.

Sunday stick-fighting at Waihi River was banned because of the outbreak and the headmaster Stone-Wigg had to bring in Sunday “tuck” himself, rather than allowing the boys to walk the short distance to Winchester. The regular church services at Winchester were also out of the question; services were held in the headmaster’s drawing room right throughout the first term.

Thus, one couldn’t really say that 1937 got underway until the second term, and what with there being no contact with the outside world we must have led the staff a terrible dance. My first few nights I remember were spent in No.2 dormitory amongst the god-like third years and I was very sotto-voce, but upon transference to our proper station, No.3, the fun began.

We had an assistant master, John Palmer who, so rumour has it, was responsible for the greatest change in the life of the school since the advent of the electric light. Whether it was Palmer who persuaded Stone-Wigg to include the gentle art of Rugby football in the curriculum, or whether the “Boss” himself decided that playing King Canute with the national obsession was doomed to failure, I don’t know. Suffice it to say that Palmer trained a fifteen to do battle with the renowned Medburians, to whom the art of rugby came as naturally as talking (or so it was rumoured).

From then on, changes came thick and fast – Stone-Wigg bought a new car after having been treated to an endless flow of advice as to what to buy, supported by the most fantastically unlikely reasons.

The old horse had died and was not replaced and I think that my first trip up to the school was the last one ever made by the dray, and thereafter it was a case of footing it! The regular pilgrimmages to church and to the Tuck shop were by now reinstated and Sunday fishing trips were reinstated now that the polio scare was on the wane. During my first year at school, the custom of having classes outside in the summer was started and the big concrete slab behind the little schoolroom was laid down not very long afterwards – this had a good effect on the health but a disastrous one on our concentration!

Jack’s piece de resistance at Waihi was in his last year, when he sat Christ’s College’s Somes Scholarship.

I wasn’t renowned for my intelligence, but I can remember Stonewigg lying back in his chair with the results. He gasped and gurgled and finally told me I had won an exhibition; 15 pounds for two years. I’ve no idea how I snuck in, because the next year at college I went for the same prize and didn’t get near it.

When Jack first walked through the College gates in 1939, the prospect of war in Europe meant military training for everyone.

As far as I was concerned, as a 12-year-old boy, this was all going to be a great adventure. There was martial music, and a tremendous surge of patriotism, and it was the same feeling for the older boys. A lot of my friends and relations joined up, and it wasn’t long before people were going into camp and disappearing off overseas. In fact, my first memory of College is the first morning of cadets, standing in a line with my back to the sun. I was dressed in short pants in the school uniform, and having been used to wearing trousers on the station my legs were as white as snow. At the end of the first line up I was horribly burnt and finished up at the school hospital with knees about twice the normal size.

At first the war did not seem ‘to touch the School very closely’, as the Christ’s College Register of April 1940 put it. The boys revelled in the exploits of E.J ‘Cobber Kain’, and stories were told of how he used to do handstands round the balustrade at the top of School House, with a fall of three stories if he slipped.

Then on April 10, 1940, news arrived of the death of Pilot-Officer Michael Barnett in an air accident in England.

He was only 19 and had left at the end of 1938, so he was known to many boys in the school. For the first time, the World War One procedure was followed in World War Two: ‘The whole school assembled on the Quadrangle after ordinary morning Chapel when the news was known, while the flag was broken at half-mast and the “Last Post” was sounded’. A second, even more shattering blow was the news of another air accident, this time to the boys first hero of the war, ‘Cobber’ Kain, in June 1940.

The effect of the war on the school was initially pretty negligible, but it wasn’t long before the ration books came in. Sugar, tea, meat, petrol and clothing – all the major imported stuff started going on to these books. When we heard about the evacuation of Dunkirk in May, 1940, there was this sudden, frightful feeling that the British Army of around 200,000 men would be cut off and we’d be left helpless. The Government kept mouthing platitudes that everything was alright, but then the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill came on the air and told us there would be blood, sweat and tears, and our backs were against the wall. Then we had a very tense couple of months waiting for the Germans to invade. It was particularly bad during the holidays when we had access to the radio, with all the awful stories about what was going on. Everyone getting gloomier and gloomier listening to these bulletins, with London completely on fire at one stage.

Cadets became a serious business, and soon parades were held twice a week instead of once. Late in 1940, the boys lost their uniforms and rifles to the Army. The loss of the uniforms, which were like sandpaper, the boys could endure happily; the replacement of the rifles by Boer War carbines which were much too ancient to shoot was not so popular. In April 1941 they got the sandpaper uniforms back and eventually enough rifles; 303 and .22, to practice shooting. Even before the war, black-out regulations were enforced, and boarding houses had to be masked each night with black frames of tarred paper.

Japan’s entry into the war in December 1941, increased concern about the possibility of air raids and even invasion. Some parents were so nervous about a possible attack that the headmaster, Mr Richards, who thought the boys would be much better to stay at school, drew up a scheme for the evacuation of boys to outside Christchurch.

Jack recalls having his bicycle inspected and hard rations ready for the 34-mile ride he and four North Islanders were to take to Whiterock. It was a grim time.

They would play the last post and lower the flag to half mast on the Big School library… the awful saga of those who were killed or missing. We didn’t talk about it much, but it was an awful feeling of…well, you just repressed those feelings. But I certainly was in tears several times. You couldn’t help it, particularly if the news was about someone you knew or admired in the 1st Eleven or whatever. It was bloody terrible, it really was. There was pride in the job they had done, but in general it was a feeling of absolute dismay.

In the first term of 1942, air raid trenches were dug in zig-zag pattern along the river bank during P.E classes and late one afternoon the whole school tested out the system by sheltering there.

On Sundays, boarders dug shelters for the aged and ill; Jack dug one for the New Zealand cricketer J.L Kerr, who had pneumonia, and still has the book Kerr gave him for his work. The only invasion at College was that of the Upper sports ground and the Gym, which began in June 1942. Radio masts and tents appeared on Upper, Harley-Davidson motor-cycles roared in and out of the College gates; and the Gym was taken over by the signallers, who slept there.

The Big School building was used as a gym instead, and there was no rugby on Upper for the 1942 season.

In the Dining Hall, with rationing the food was bound to become stereotyped, though there was still plenty of it. All boys had ration books, with coupons for meat, butter, sugar and tea. Boarders invited out for Sunday meals were expected to take some ration coupons with them. The maids, smartly dressed in their black uniforms with starched white caps, cuffs and aprons, and under constant appraisal by the boys, all but disappeared, being replaced by the boys themselves, who began to do much of the clearing and washing up. In the winter term, boarders used to receive cocoa and biscuits, but by 1942 cocoa was unavailable and biscuits were scarce, so tea was put back to 6pm instead of 5.30 and one prep was done from 5.25 to 5.55.

When boys weren’t thinking about the war, school was mostly about creeping your way up a complicated pecking order.

By Jack’s third year, 1941, he had made the Second 11, where he kept wickets to Tony MacGibbon, who was later to become one of New Zealand’s best fast bowlers. Still, he initially made “little impact” in rugby and athletics. In 1942, as a 6th former, he moved into Jacob’s House “Winchester” study. The rooms were unique, and much envied by other Christ’s College boarders, for their private cubicles. It was a tremendous lift. Finally you had some form of privacy. As a sixth former, you suddenly started to be someone.”

There was still plenty of work, however. In the first term of 1942, boys spent Sundays digging air raid shelters.

Loved playing “fives”, especially because it kept you fit, but early morning swims in the outoor pools were a nightmare. “My desire for swimming was almost killed by the College baths.”

In the 6th form, he was part of the agricultural class, which went out to Lincoln College once a week. Lectures were in the morning and labouring was in the afternoon; jobs such as grubbing thistles and gorse in cow paddocks.

“We were basically doing Lincoln’s donkey work as a sort of war effort, but we also had to grub thistles at Lyttelton. That work was just a waste of time and money.” The lectures included 6 weeks on the lifecycle of the brown beetle.

In the winter of that year, 1942, his arm became infected and severely swollen. Initially out cold in bed, he woke up lying on the springs of his bed, ranting and swearing in a fever.

“I lay in bed for a week and they were close to losing me at one stage; I really was at death’s door and apparently there were prayers for me in the College chapel. When they operated they drained well over a pint of poison. I wasn’t fit again for weeks.”

In his final year, 1943, he was captain of the 1st 11 and Officer Commanding of the Cadets. He was also head of Jacobs House and secretary of the Games committee. For a few months he was also president of the Mysoginist’s Club – an informal group of women haters’. But then he met Norna, resigned from the club immediately “and never looked back”.

Jack also spent four years in the College choir, first as a treble and later a bass. But rugby and cricket lingered in the memory the most.

In 1943, the Timaru Boys High School 1st 11 also had their first win against College since 1930, despite Jack, as wicket-keeper, dismissing six batsmen in one innings.

The same year, Jack was part of the Christ’s College 1st XV that bowled over a much-heralded Christchurch Boys’ High School side. “We were an ordinary bunch of boys, and up till then Boys’ High had won every match that season by 40-60 points. The atmosphere for the College game was terrific, especially with all the old boys there who had come back from the war, but everyone thought we were odds-on-losers. But the lead changed four or five times during the game, and at the end we came out 8-6 ahead. There was just an extraordinary feeling of disbelief.”

Sixty years after the game, all 15 players who played in that game were still alive. Every decade for the first 50 years, the entire College team gathered for reunions and posed for a photo in the same position as the 1943 picture.

Still, like many of his mates, the war cast a long shadow in his memory. Many Old Boys came to Chapel in uniform on their final leave and often visited their old houses. Jack remembers David Monaghan coming into Winchester Study, Jacobs House, on his final leave and in what seemed like a few weeks he was dead – he died of meningitis in Italy in January 1944.

During the war, 1206 Old Boys and eleven Masters saw active service, of whom 177 Old Boys died. The “Register” of April 1940 announced proudly that three Old Boys in the R.A.F had been awarded the D.F.C; by the August all three – E.J Kain, G.W.F Carey and K.N Gray – had been killed.

Sometimes the ‘Last Post’ ceremony struck very close to home. Shailer Weston happened to go into the School House common room during Chapel and found a junior boy there. Asked why he was not in Chapel, the boy said he had permission not to go. ‘Why?’, asked Weston. ‘Because my older brother has been killed’. He had been excused so that he would not have to hear his brother’s name read out in Chapel or attend the ‘Last Post’ outside Big School. Weston asked no more questions.

References: College! : A History of Christ’s College. By Don Hamilton.

History of Waihi School 1907-1982. By John Collins.